Pre-Interview: Paolo Cirio

Pre-Interview: Paolo Cirio

In anticipation of NOME Gallery's group exhibition, Evidentiary Realism, we spoke with curator Paolo Cirio about his development of the concept, the aesthetics of presenting and revealing evidence, and his own investigatory process of putting together an exhibition of investigative art practice.

When did you begin to work on the concept of Evidentiary Realism, and what was the impetus for pursuing this particular direction in your practice?

I started to work on it about 2 to 3 years ago. I already had a feeling about it, but after Snowden, I became convinced that this was the trend. There were an increasing number of artists engaged in it, and I noticed how the audience as well was responding to these events. I had the idea and then I talked to Luca Barbeni and he believed that it was possible to produce the show. I had also done a few projects and was myself engaged in this informative kind of art practice – concerned with the release of data, WikiLeaks, and mass surveillance.

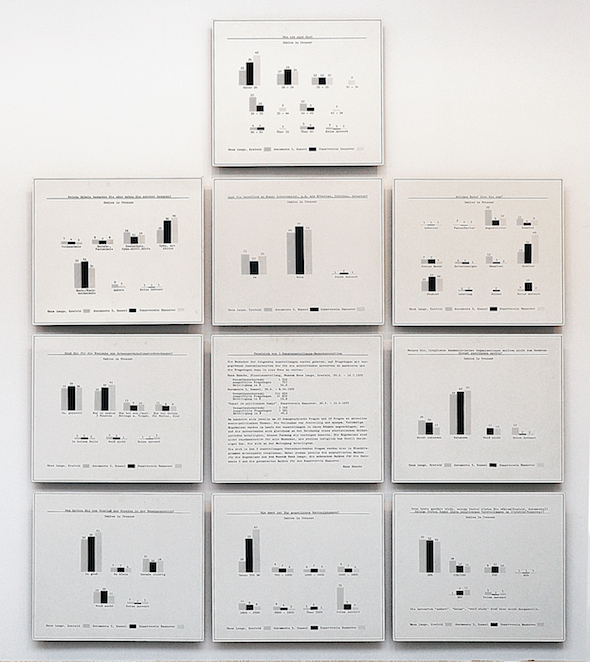

As curator here, I didn’t want to interfere, or insert myself, and I also don’t want to lead it too much. I don’t think of it as an art movement, but more of a tendency and an effort to bring together artists that have common practices. They do form a community, and mostly know each other. At the same time, however, Hans Haacke is 40-50 years older. That’s also why I wanted to do this project; I felt there was a missing link. There are a lot of artists doing this now, but there had not been any effort to bring them together and to get to the ontology of this practice. I’m now trying to find out whether someone could have come before Haacke, or whether the trajectory is a little longer. But, so far, I would say he was the first. It was also at that time that the social, economic, and political developments started to be of this sort of complexity and to expand – technologically, geopolitically, and legally. Then, artists responded to what was going on – like Mark Lombardi, for instance. At the end of the 80s and 90s, the financial system was taking over and the political system started to use it, and information was becoming available. Now, because of the scale of these developments and the complexity of technology – with geopolitical, economic, and legal complexities expanding – there’s also an expansion in artists engaged in these practices.

Hans Haacke: Comparison of 3 Art Exhibition Visitors' Profiles, 1972-76; Ten silkscreen prints mounted on aluminum. Courtesy the Artist.

Had you done or been interested in curatorial work prior to this?

I had done some, but not really of this scale. I had done a conference in New York a few years before this and some other small panels. I’d always been interested in art history and had read a lot of criticism and philosophical thought. And I was interested in questioning things, because that’s very important. It was also a development within my own thinking, since this realism is new for our generation. Some former works and reflections were closer to the opposite of realism, in a way. Now we talk about the decline of post-structuralism, and it’s actually almost contradicting something that I was studying and doing 10-20 years ago. For instance, I used to read a lot of Jean Baudrillard – I’ve probably read about five books – and now I consider that to be a part of the past that doesn’t apply to what’s going on today. But times change; you cannot always apply the same thing. I think it’s very important to make this point: that you cannot apply the same structures of 20 years ago, because we live in another dimension. Even though there’s a strong legacy and people invest a lot in that idea, we should also move on. I think audiences are moving on, as well as artists – aesthetic sensibility, in general, is changing.

Since its first iteration in New York earlier this year, how has the project developed or changed in the exhibition here at NOME?

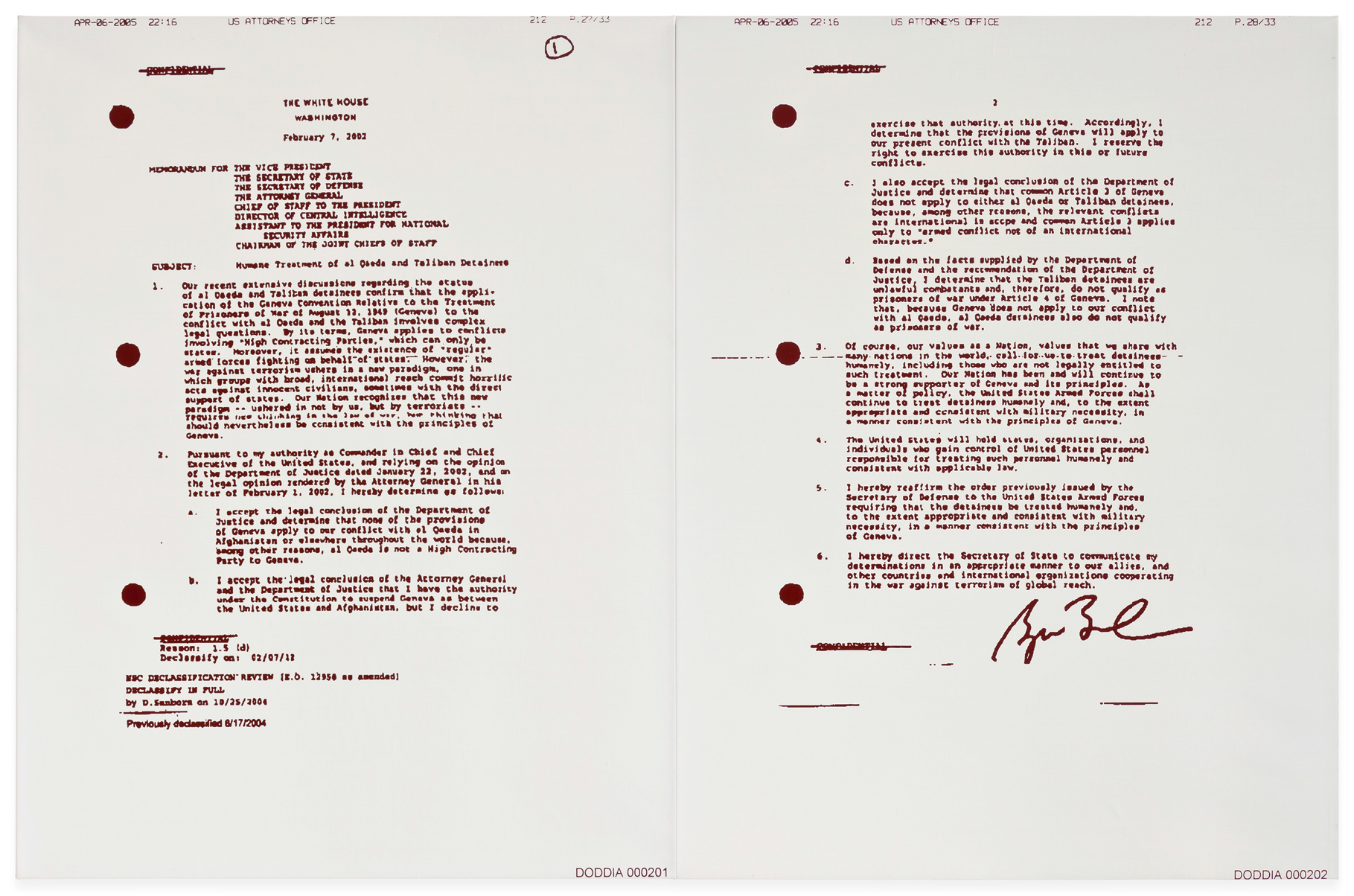

The main development is Jenny Holzer’s work, which I didn’t have in New York. For me, that was very important, because she’s one of the first who talked about state secrecy and the redaction of documents. She’s also very well respected by all the artists that work in that field. I’m also very lucky and grateful that I managed to have works by Mark Lombardi and Hans Haacke again – these works are very rare and very difficult to find. It was a process that took months; it really was an investigation within the investigatory practice. Otherwise, the artists of NOME have pretty much remained the same. There was pretty intense research surrounding the work of all these artists. For instance, James Bridle has a pretty big body of work, but this video, Seamless Transitions, was the one that fit nearly perfectly within the concept; it’s basically a forensic investigation of an invisible, secret site in the UK. I had also received some proposals from artists that I had to decline. And of course, it’s also based on the availability of works. Overall, I find this show to be even better than the one in New York, because we didn’t have Holzer, and the work of Lombardi was a smaller one – a sketch. It was great because it had Donald Trump in it, but the work of Lombardi that is shown here is the most well known of his, because there is the connection between George W. Bush and Osama bin Laden.

Can you discuss the notion of enhanced, or amplified, realism that you refer to in writing about the concept, and the ways in which this manifests in the works in the exhibition?

For me, the amplification of realism is not only about the technical, but the epistemological capabilities that we have today in investigating reality. If you think about realism in the classic sense of the term – in a painting or photograph of a social situation – the medium these artists used was, for instance, a camera, and they then added a philosophical framework to that picture. Today, it’s not only the photo camera or the painting, it’s a set of technological advancements that can come in the form of satellite, 3D scanning, big data, and so on; and the social sciences, or social theories, that you can apply to the representation are way wider and deeper. That’s why I talk about an amplified sense of reality. Everything is then synthesized within one picture, or installation, or video. That is the visual form of realism – of reality. I also have this idea that the artist unveils secrecy and complexity in conducting this investigation, using these techniques. They can actually show something that we don’t usually see. At the same time, however, it’s also true that those systems – those realities – are so complex and so manipulated that you still cannot really see them. So, what the artists may try to show us is just a little glimpse. It really depends work by work: in some cases, they did manage to reveal something; in other cases, they reveal just the techniques, the idea, or the total secrecy. Holzer’s work is the only one that’s not redacted at all. In Josh Begley’s work, on the other hand, there was a leak of data from the NYPD, consisting of thousands of pictures. In that case, the data was released and the full expansion of the program is now public; that secrecy is over, so you can actually see it in its entirety.

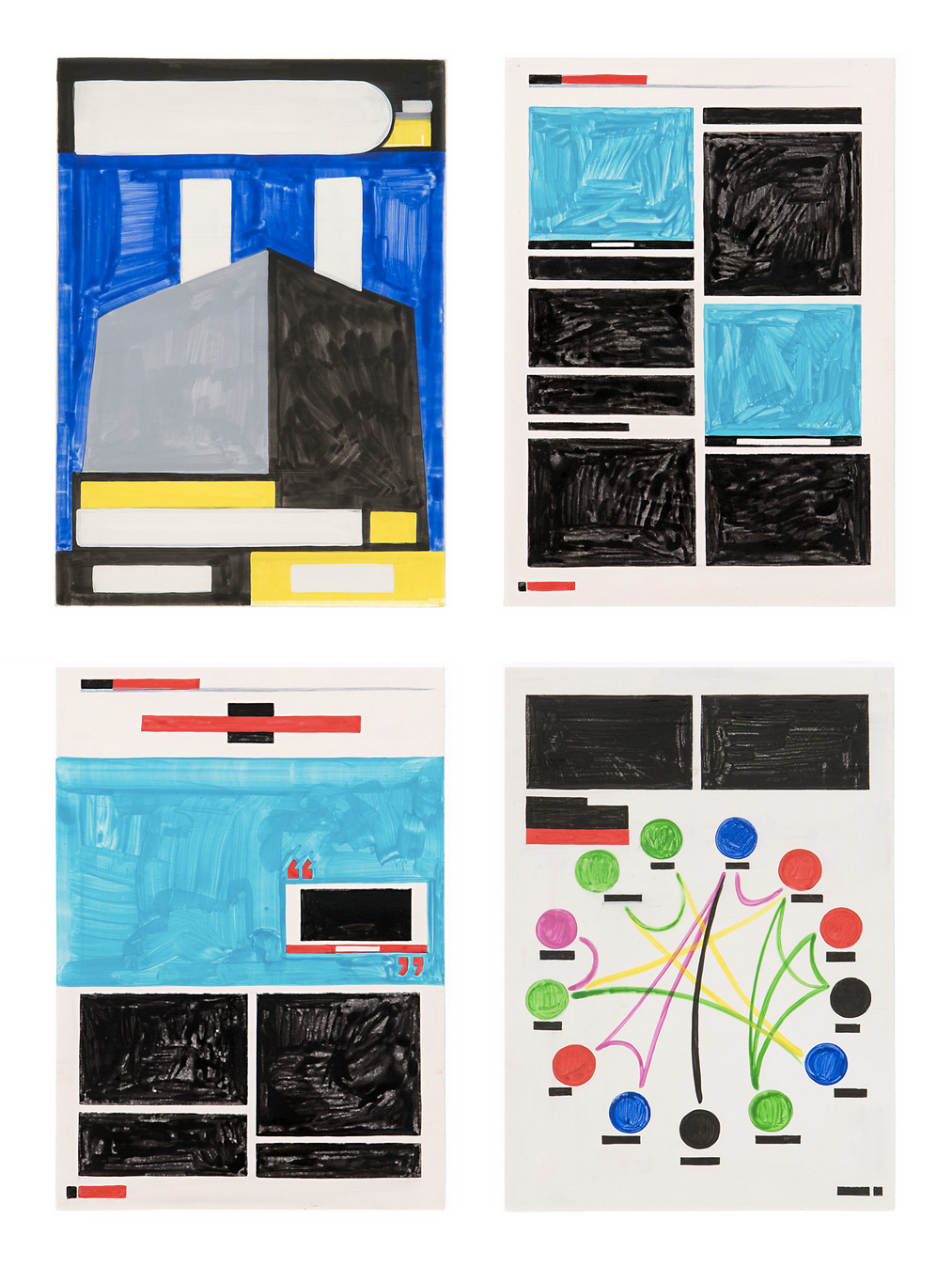

What are some of the aesthetic strategies that work to expose, or make accessible, the different forms of evidence presented?

In Navine G Khan-Dossos’s work, for instance, she abstracts the linguistic devices of ISIS’s magazine into graphics. She takes out all of the content and just shows the linguistic structure and how it plays a role in propaganda, or functions as evidence of rhetorical devices. This is also the case in Kirsten Stolle’s work. Sometimes it’s not about the content – the actual data – but the infrastructure. On one side is the forensics of information in general – looking at the data, or the picture, and analyzing it – and on the other is the linguistic instrument – the language. It is not always the content that matters, but how it is framed to manipulate the meaning of that particular thing. In Stolle’s work it’s that of Monsanto Chemical Company’s advertising, which is public information – they were advertising in a major magazine – but she highlights its linguistic manipulation. That’s the secret device that's revealed; or, perhaps it's the complexity of that device. Her technique is to redact, but she uses this redaction to reveal: by blacking out all the unnecessary information, she’s basically underlining what the message actually is.

Navine G. Khan-Dossos: Expanding and Remaining, 2016; Gouache on board. Courtesy the artist and NOME Gallery.

Considering you explore similar themes in your own art practice, in what ways does your approach differ from that of your curatorial work in this project?

I’ve always been interested in these kinds of practices – such as documentary and informative work. I could probably have a work of my own in this show. However, my work sometimes has another level – that of agency and participation. There is a kind of agency in some of the works in this show, but to some degree, they speak for themselves. It’s like when a journalist conducts an investigation and then publishes the report – it doesn’t mean that that dossier is political, per se. It just reveals what the journalist researched and found out. These works are like that. It’s not really political art; the artist does an investigation, makes an artwork, and shows the audience what they found. The audience then looks at that, feels or understands something, and takes whatever they want from it. I don’t call it political art. It’s political in the sense that a newspaper is political: it might have an orientation, but it tries to remain independent from any political affiliation. This is what I try to have in this show. In my work I also do that, but it’s more complex, in a way, because I try to have more edges.

What other plans do you have for developing the platform or continuing the exhibition series?

I’ve discovered it’s very complicated to be a curator – and it’s already complicated enough to be an artist. For this project, I've had to sacrifice a year of production of my work. But now that the groundwork is laid, I am thinking about potentially commissioning a new work by a new artist, perhaps organizing panels, having a virtual exhibition, or making an online magazine. Another effort that’s being made is to bring this show to a non-profit institution or museum. There isn’t anything scheduled yet, but I am working on it.

James Bridle: Seamless Transitions, 2015; Digital video projection, one channel, 5:28 min.

***

Evidentiary Realism NOME Gallery Opening: December 1, 2017; 18h 2 December 2017 - 17 February 2018 more info