Have you met... Robert Henke

Have you met... Robert Henke

Robert Henke is a dear old friend of Berlin and a figure unavoidable in electronic music circles since the 1990s. Alongside his Monolake releases with Gerhard Behles, he is known for the music, performances, and installations he has been creating under his name. His latest projects are mostly audio-visual, making use of high-powered lasers. The most recent one is collaborative work with Christopher Bauder called "Deep Web", currently installed at Kraftwerk for the CTM Festival.

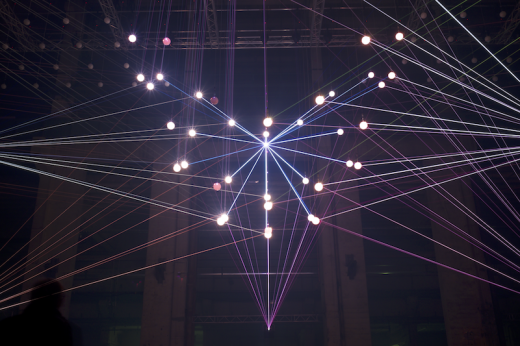

"Deep Web" is an immersive installation using 12 high precision lasers and a matrix of 200 moving balloons to create a dramatic 3-D sculpture of lines and dots floating in space. The choreography is synced to a musical score played back in 8-channel surround sound. Even the most detailed description will not, however, give you the proper impression of this monumental work, which relies heavily on the interference with the space - the raw, cavernous hall of the former power station. With its world premiere at the venue valued as Berlin's cultural landmark, "Deep Web" is likely to become one of those experiences boldly highlighted on timeline of the local scene.

While the festival brings a truly international crowd of artists from all over the world to Berlin, it brought Robert back home where it is most unlikely to meet him due to his frequent travels. We were lucky enough to talk to him in person immediately after taking part in his "digital meditation", as one of the visitors described it aptly.

Tell us more about the installation and the perfomance "Deep Web". What was the starting idea, and how did you come to collaborate with Christopher Bauder?

© Robert Henke

Christopher and I are collaborating for a long time. We started in 2007, working on a project called "Atom" which was in some ways similar to "Deep Web". It is a matrix of 64 balloons which are illuminated and driven by motors. I control the lights in the balloons and the musical score, and Christopher built the machinery to make it possible. In this case, Christopher built the system hanging here, which allows the white balls to move around in very high precision. It was Christopher's idea to use lasers to illuminate them. In a way this is very much a Berlin success story, because there is a third person involved – Michael Solinger, the CEO of the laser company located here in Berlin, who programmed the lasers in such a way that what we are doing here is actually possible. It is something that has never been done before. It was a big technological effort to make this happen. Working with Christopher is fun because he is someone who is always pushing things to the limit, and always very confident that we will reach a point where impossible things are possible. He had the idea to do this, and then we started talking about structure and how to present it. Originally the work was commisioned for Fête des Lumières in Lyon in November 2015, but the whole festival has been cancelled after the attack in Paris. At this time the project was already finished, and we didn't want to just leave it, because a lot of programming work, coding and thinking already went into it. So we approached CTM. It was very clear that this has to be the space. I am very happy that it worked here because, as someone who is involved in the scene in Berlin for almost 25 years, it makes me very happy to see a CTM collaboration happening in Kraftwerk. To me this is more than just doing an installation here. It is also doing something for two festivals and institutions which are important for this city.

You worked in collaboration with other artists before, and of course there is probably the most notable one – Monolake with Gerhard Behles. How do you feel about collaborative work in general? In what way is it advantage, or disadvantage to share the creative effort?

In general, I feel that collaborating is fantastic if you find the right people, because it is very easy to get lost in front of a computer screen. For instance, one reason why I like working with Christopher is that he is in a good way very judgmental. He says what he likes or doesn't, and he always has a reason for it. This is very helpful in a collaboration. I think the most succesful collaborations are the ones where two people have a common idea, but sometimes also very different ideas. It creates a nice feedback where really interesting results can happen. Sometimes I like working alone because I have complete control, which is nice too. Everything is 100% the way I want it, but the risk is to get lost in details. If you work with other people then the focus is on the essence. For this project it was absolutely necessary because we had very limited time to do it.

How has your practice shifted throughout your career? Was your starting point in science or art, or somewhere else? Do you even think about these different things separately or was it for you always a sort of a hybrid you wanted to work with?

I come from a family of engineers, so it was very clear that I have to become an engineer. For me personally, it was always also very clear that I am interested in art. I went to museums when I was a little boy, and I was fascinated by abstract art and sculpture. Then I discovered electronic music. When I moved to Berlin it was just at the right time to become part of the techno scene. I moved here in the early 90s, and I was experiencing the evolution of electronic dance music. I studied computer science and sound engineering. So, it was always a mix. For a very long time I was a bit confused if I am more an artist or an engineer. At some point I understood that it is not a question if I am more one or the other. My artistic practice actually involves engineering and that's just how it is. My artistic expression lies in writing software, or soldering cables if necessary. It is part of my artistic job, as much as having the right ideas and writing concepts.

Considering all the different types of spaces you performed or exhibited at, what is your approach to art and music making in relation to the space?

For me the space is tremendously important. I like all the details. I spend a lot of time thinking about the placement of the loudspeakers, which type of loudspeakers... I spend a lot of time adjusting the sound, but also looking at details such as: when do people get in or out, how do I end an installation. At the end of the day I perform the installation here, and I do that every evening, to make sure that it is not just someone turning off the switch and bang, it's gone. I like the people having an experience. And this experience is always connected to spaces. And again, techno culture plays an important role because it was always a culture of exploring spaces. The very first Tresor, which was not in this building but in Leipziger Strasse, was in a former tresor room of a bank. It was special to go down there in the basement because it had a special energy. That was true for all the early techno clubs. In every space the architecture was as important as the music. And for me as well, I can't separate this. I can't play techno in a club where the next day there is a rock show and noone cares about anything else but the money. Those places exist all over the world, and they don't work for me. I need a space where I feel that what I do in the space and the space go together. Putting this structure up here makes complete sense in this regard.

You used to teach at various universities, including the Berlin University of the Arts. How did that affect your way of working?

I learned a lot from my students. If you want to be a good teacher, you have to know more that the students. If you have good students, they know a lot, so you always have to keep learning for yourself. I had a student who had ideas which were 500 kilometers away from my own. I had endless discussions with him. The more we discussed, the more I understood that his point of view is completely valid. It is just a very different system of thinking. But within its own system it was completely closed and valid. I was very impressed by that, because I noticed that you can actually look at something from a completely different perspective, and it can be completely correct. This is why I am fascinated by the arts as a counterpoint to engineering. In engineering you have a very fixed set of tasks, you have a goal and this goal is very clear – this thing has to work exactly as specified. In the arts you don't have that. There you have the idea, and the idea might change in the process, and you might not even reach it at some point. These are all things that teaching helps you understand.

Can you think of a recent show that really impressed you?

Last great thing I saw and really impressed me was a piece of 20th century classical music by Helmut Lachenmann, still living composer of orchestral music. Unfortunately I don't know the title of the work. I was at the symposium in Essen, and I happened to get tickets for the Philharmonic Orchestra there, and they played this piece. It was just stunning, what kind of sound, spatiality, timbre and structure you can get out of orchestra. For me this was far more important than releases from 90% of techno artists. It was really something that touched me because I didn't expect it to be so amazing.

What is your view on the current electronic music scene?

What I noticed is the fact that producing electronic music became affordable for a lot of people. A lot of very young people do really crazy - in a positive way crazy stuff, and I'm very happy about this development. Doing electronic music was always in some way connected with a severe financial investment. Actually not in the early 90s with early techno, because this was music which was so raw that it was possible to do it with very limited equipment. But to do something according to studio standards was very expensive. Nowadays it's not. This leads to the fact that people can actually create music with very limited financial effort. But this is only one part. The other part which I find amazing is actually the internet. The fact that everyone can publish music and find an audience all over the world. I had a concert in Lima, and I spoke to many local Peruvian artists, and I find this truly amazing. We talk about very difficult political situation at the moment, about severe cultural clashes, about religious fanatics. But at the same time, we have a grown international community of people all over the place, including Kairo, Syria, or whatever country, where people are sharing the same ideas about electronic music. That is I think more important than the latest releases of famous artists.

What can we expect from you in the near future? Any projects you would like to announce?

I have a gigantic list of half-finished music which I want to finish when I find time. I plan to release a Monolake album this year, I plan to release drone ambient album, I consider releasing material from the "Deep Web" installation on a CD... Lots of plans!

: : : : : : : : : : : :

"Deep Web" by Christopher Bauder & Robert Henke

Saturday 13 - 21h, Sunday 13 - 18h with a special live performance at 19h

Kraftwerk / Köpenicker Str. 70, 10179 Berlin, U Heinrich-Heine-Str.