Surface and Superficiality, part IV. Berlin Biennale (2)

Surface and Superficiality, part IV. Berlin Biennale (2)

The Palimpsest of Democracy - on "The Draftmen's Congress" by Pawel Althamer at the Berlin Biannual 7

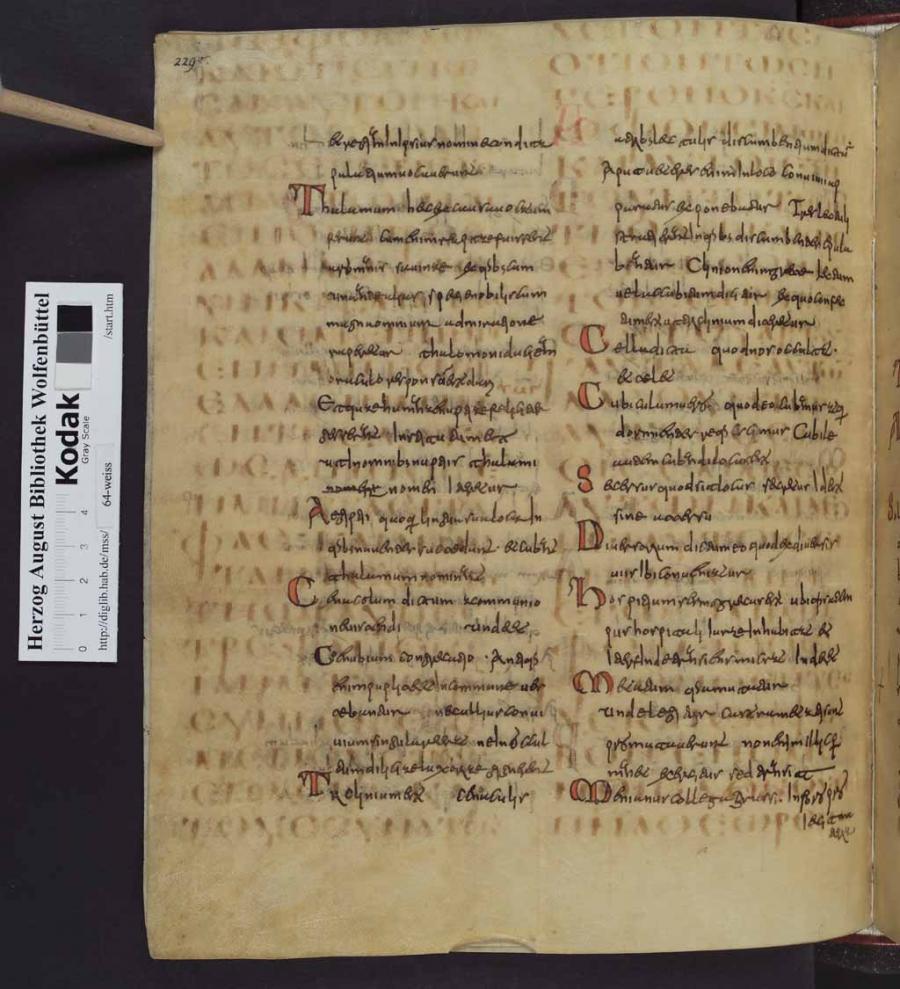

Several of Gitte’s texts in this series have been concerned with the repellant, slick, hydrophobic, etc. surface in design and technology as a symptom of an order, which also in wider social and political situations let the “user” slide off the surface, or forms her relationship to and interaction with it in certain ways. The mass of possibilities in e.g. an iPhone for adding a personal touch, or designing the interface, hide the actual lack of freedom, which has been reduced to the possible choices, so that a genuine appropriation of the object becomes impossible. The opposite would be a surface, which is open for real interaction, into which the user can really inscribe herself.

“The Daftmen’s Congress,” the contribution of Pawel Althamer to the Berlin Biannual 7, in the Skt. Elisabethenkirche is described as a participative work, which invites the audience to express themselves, leave their mark, by drawing, writing, painting on the walls and floor of the former church, which have been painted white for the purpose. They are encouraged to “react to issues like current politics, symbols of power, religion, economic disasters, and so on,” as well as the expressions of the previous visitors. The aim of the work is to activate the visitors and turn them into participants, making them part of a continuous discussion. “In this project, authorship, hierarchies of expertise, and qualifications are blurred into an enterprise of illustrating excess, which is free and open to all.”

The big, democratic and free discussion envisioned by Althamer never materialises. Instead of an exchange of opinions, with the aim of learning, what we see is a large amount of individuals, who all want to realise themselves at the expense of the others. Participation stays on the surface, on the palimpsest of the wall, which is covered again and again with the various expressions of opinion, self-expression and attention-seeking. When the signs are overlapping, the individual putting her mark on top of, next to, or between the others, without any necessity of actual communication, the participative work becomes an image of the individualised post-democratic society. There are no hierarchies, no limits, the individual can unfold herself creatively – ought to do it – one is overwhelmed by voices, which all say their own thing. But in the end what is lacking is what would make it an actual critical work, namely the statement that goes further than stating that each individual can have an opinion on some issue. The opinion of the individual becomes unimportant, at the same level of all other opinions. There is no antagonism – a necessity for political exchange – because all expressions (of anything) are equal.

In this way, “The Draftmen’s Congress” shows where the whole of the BB7 fails. Its basic premise is that art should engage itself directly in politics and work for change in society, without going the roundabout way over being art first. Art should “purify” itself from its pretension of aesthetic autonomy and finally take responsibility for its political interests by dissolving itself into political activism. Althamer’s work wants to eliminate the audience and make the people take part and hereby dissolving the artwork into a discussion. This is the artist’s longing for the authentic, the direct, the real. The artwork should be measured on the effect it has, not on formal, aesthetic or conceptual qualities.

Artur Żmijewski interprets art’s autonomous aspect as its fear of intervening directly into reality, and grounds it in art’s involvement with various totalitarian regimes. In my opinion, it is exactly what AZ criticises in art that makes it into an important critical tool. The aim of art is not to dissolve itself in activism (for that we have activism). Its role is to be art, its possibility for searching for critical forms and its negotiation with its always problematic position between autonomy and social fact. Its strength is its insecurity, posing questions without having the answers, its openness and that it doesn’t aim for a specific efficacy. That the curators of the BB7 want art to be efficient makes it into just another symptom of the late capitalist obsession with profit, efficacy and achievement and is expression of a functionalist rationalism, inserted into art in the form of curatorial discourse.

The mishmash on the surface of the walls and floor of the church is a reflection of the superficiality of the BB7’s interpretation of art, politics and their intersection. Express yourself, be creative, no hierarchies. Herein lies in a way what could be described as one of the horrors of our contemporary culture: Democratic excess as a spectacle and the colonisation of autonomous expression by key figures of late capitalism.

- Gitte Bohr.