Fette Sans The night would lie during the day

Fri, 22 Nov 2019 18:00-21:00at SOX

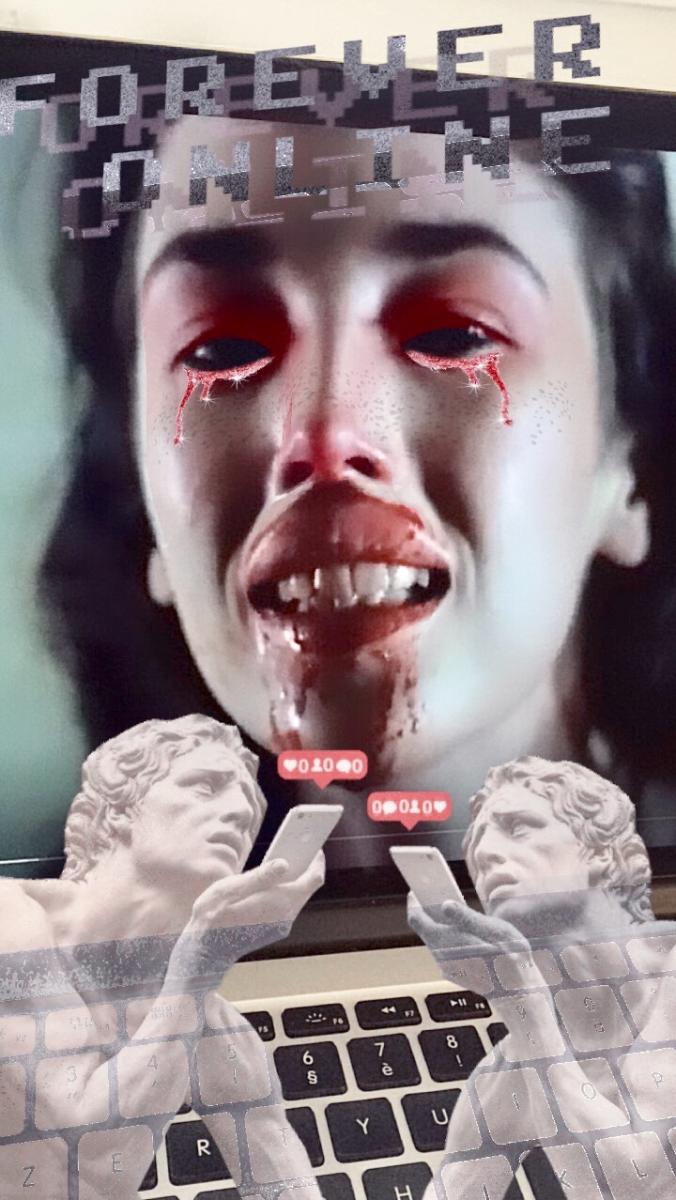

Fette Sans The night would lie during the day

A person climbs the Acropolis and sees the Parthenon.

This building has its viewer very firmly in mind. The building knows this viewer intimately. The Parthenon’s many ‘optical enhancements’ testify to this. Its columns, which taper because they were cut to follow the curve of a circle four thousand meters tall. The six centimeter bulge carefully laid into the foundation of its front steps, a bulge which every stone above follows, just below the threshold for our perception of curvature. Every visible straight line, in fact, is curved and every flat surface subtly out of level. And all of this was done to create the illusion of a perfect building. (The illusion of actual straightness is possible only through curvature, something every homosexual has always known.)

And all of this was done for democracy. Not democracy as we understand it, but democracy as the principle of absolute equality before the state. Athens knew its people so well that its buildings could correct for every citizen’s heritable defects of perception. To look at the Parthenon, even now, is to feel these defects corrected and then marshalled to the greater glory of Athenian democracy. It is what being irradiated with equality feels like.

It has been surprisingly difficult to make a less compulsory sort of structure. This was originally due to the love affair between power and the architecture of compulsion. A love that crosses all divisions: When Constantine converted to Christianity his Church needed an architecture for purpose-built houses of worship. To deflect any impression of Christian conquest Roman temples were not to be copied. Predictably, the imperial building selected as the template for all future churches was the Roman court of law, the basilica. But as the Church broke in its new power these scruples were quickly plucked out. It would be barely two hundred years before Justinian told his architects he wanted the dome of the Pantheon on a rectangular basilica, his only brief for Hagia Sophia.

But the architecture of compulsion is far more sophisticated than the crude desires of those who initially wielded its techniques. This is because the Parthenon was the first mature expression of the idea that people are what can be manipulated about them. That whatever a person may be to herself, this is irrelevant compared to what she has in common with others. A commonality that serves as raw material for a saddle, one that can be used to ride anyone it fits. The perversity of manipulating someone who comes to your structure in the spirit of congregation is very familiar to us. Pursuing human cleverness to its endpoint, whether you begin with a bald acropolis or a social network of fuckable Harvard students, is to walk toward a convergence.

A person walks down the street in Berlin. She is known by her city at least as well as Athenians were known by theirs. The city knows when she bleeds; her phone offers a coupon for menstrual products on the day it begins. The city sits on her back like a saddle. Those who rent the right to ride her do so until she becomes insane. Until she smashes a shop window, not noticing its proportions are 1:2, the same as the rectangle that defines the Parthenon’s front facade. She climbs over the shards still held in the windowframe. She kicks the shoes off their stands and into the street, tossing her own after them. She lies in the broken glass at the bottom of the shopwindow. The stale air flows out into the street. She spasms and her back arches. Her shoulders mute the squeal of glass beneath them. She screams again and again. These echo off the city.

Our experience of the Parthenon has always been virtual. It is not there in the way we think it is. To look is to be tricked. Two thousand years of furious husbandry have bred these tricks into ends in themselves, and what must have seemed like the nectar of human cleverness when it was making the Parthenon ideal has been distilled into venom. This, in turn, makes possible our universal and sunless agriculture, the system that plants an ad for tampons in a woman who bleeds. A system whose very perfection drives its beneficiaries insane. And so, if the woman seems not to lay there in the window, if her blood doesn’t drip on your shoes and the glass looks replaced, it is only because your defects of perception are well known, and easily corrected.

Essay by Lazenby