Felix Deiters The Questionnaire

Felix Deiters The Questionnaire

How does the disappearance of time influence your mood, mental health and bodily experience? Help us find out by signing up for, and sharing, our new pre-registered survey!

These surveys will track your mood, your experience of the (time) crisis, and your interoceptive experiences on that day. You can stop at anytime, and should do so if you feel any distress whatsoever from completing the surveys.

The first time she had her tarot cards read, she was told to keep her question quiet, to herself. And in this crowded bar she took a breath of relief and with sedulous silence, she uttered nothing. Oh, how good this felt to be offered both the question and the answers, she had thought.

Considering how much biometric data she had shed into the world, it was astonishing how much more diffuse she was with information. She told herself this spoke of a desire to inhabit other identities, of voraciously collecting stories, of wanting to remain odd-angled, hazy-like, being based nowhere-in-particular but here, and of always preferring another scene altogether, like a second opinion to her own thoughts. Anything but a straight answer, and never settling on a favorite color. Not that she didn’t have one, she simply preferred to complicate impressions made of her.

But a questionnaire isn’t a manifesto, I told her.

In 1617, an interrogatory comprising eighty-four items guided the commissioners of Eichstätt in Bavaria in their investigation of suspects. Some of the questions were grouped under topics, such as “Diabolical lust” or “shapeshifting.” Under the latter, one of the questions asked was “Whether she did not change into other forms; why, how, when, and by what means did it happen (no. 75).”

In a world where death came often and unannounced, I imagined how such questions required precise answers when the only guides were shaped by dictated prayers and confession-by-fire.

A questionnaire would have to be cast like a spell, she said. And the answers would bear the contours of a knife found in the crease of a striped couch. Words thrown like insults to exercise one’s conjured slang—the bastard tongue lovingly excoriating the mother.

Or Panacea fucking Epione, I said over her laugh.

She wanted to know if there was this one lie I kept, and would always reach for when trying to give a satisfying answer to a stranger felt like watching my doppelgänger reach into my organs with a grin. I realized that I didn’t possess such a handy tune to sprinkle. I already killed the louche fucker, I probably answered instead.

I take that you have one to recite, I asked.

Yes.

She had always loved taking and trying on things from her friends’ closets, or from a lover’s bedroom floor, a shirt worn the night before preferably, and when they would say you look good, she would always believe it. She thought how such gestures were templates to her own advice column, or towards an entire self-help book for casting foolish yet sensual responses when each question is a riddle. After all, advice—whether unsolicited, unwarranted, or desperately sought—appeared in ancient philosophical treatises, and medieval medical manuals, before it became the golden smear of Facebook’s actually infinite News Feed.

It was the hospital regime that produced the first sets of standardized protocols for the collection of information forms to be filled in by doctors. Volker Hess and Andrew Mendelsohn have written about “the technology of paper pre-scribing,” namely, blank sheets ruled in columns to obtain particular data. By the end of the 18th century, hospitals in Berlin and Vienna used these to record patient admission, diet, and discharge (or death). More detailed diagnoses and treatments for each patient came to be added, or recorded, on separately configured sheets or in journals. In long-practiced disciplines, such as medicine, the categories or topics written at the top of the columns – symptoms, diagnosis, prognosis, cure, etc. – functioned as implied questions.

I told her how much I loved to look at my multiple reflections formed by opposing mirrors in the entrance halls of the old Charlottenburg apartment buildings. Like a relentless acquisitor of circumstances, you seem to extend into the infinite when in reality you get progressively darker and fade into invisibility, long before you even get to the end. I remember how she looked at me as if I had just hurled an occult formula she could deviate into a questionnaire. It’s in the way mirrors reaffirm body consciousness by gesturing deceptively towards our inherent failure of communication—how my reflected body would be saying no when I wanted yes.

Is that what being in the world means to you? she finally asked me.

Maybe.

The push and shove of wanting, immersed in such an unstable, expansive present. How does one sequence self disagreements? I responded.

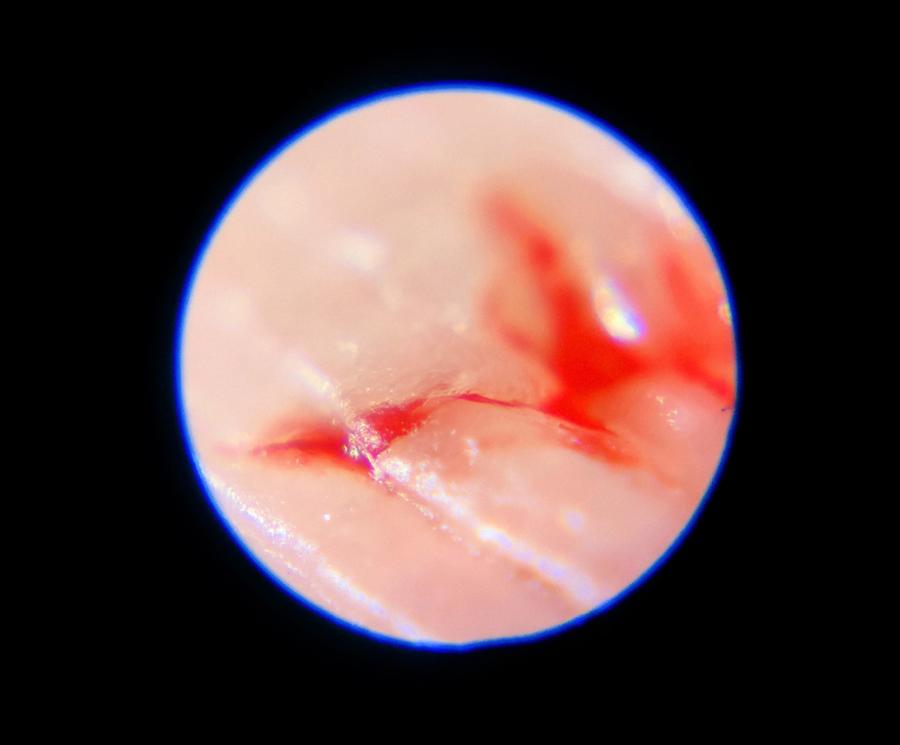

Eventually, I told her that the questions I answered best were always the ones conferred like orders by a lover, questions without interrogation points, permissions really. As if possessing a strange talent like drawing blood simply with their fingers touching my skin. Conjuring veins for a laugh, or a fuck, and never expecting words.

She would attempt a dispute, insisting that a questionnaire is always like an armor to the one who asks. The one who asks doesn’t have to endure any of the arrows yielded in return, she yelled at me.

I remember how I stroked her hair, consoling her fantasy of opting out by saying that she needed to commit more dramatically to the source of the conflict by spending even more time on Quora. Finally, she kissed me with a smile.

I remember having said something like how in his genius, Bob Flanagan had gotten rid of the power of decision-making by stealing all of the arrows. Turning his curse into something better than any audience when he had raised this army of Saint Sebastien longing for his embrace.

Perhaps questionnaires are the ultimate aporia between words and meaning, they suggest the most imperceptible forces, from moon tides to the incomprehension of decay. They force a collaboration like a hieratic plot, so deceptively arbitrary yet often bearing a scheming motive, that when a question eventually satisfies the curiosity, it induces the rattled wish to have had an entirely different one asked.

Did I only give you love when you were in pain?

I don't know. I was in pain so much of the time.

Excerpts from Daniel Midena & Richard Yeo (2022) Towards a history of the questionnaire, Intellectual History Review, 32:3, 503-529, DOI: 10.1080/17496977.2022.2097576

Text: Fette Sans