Fourth State of Matter: raster-noton's "white circle" @ Halle am Berghain

Fourth State of Matter: raster-noton's "white circle" @ Halle am Berghain

It is ironic that the one time in Berghain I am allowed and encouraged to take photos, the things that I am seeing, hearing, and feeling seem especially impossible to capture. This is a testament to the success of Raster-Noton’s new audio-visual exhibit “white circle”, which opened yesterday in Halle am Berghain in celebration of the label’s 20th anniversary.

Of course the two-dimensional image and the thin, monochannel recording devices in most cell phones are woefully insufficient in documenting the power of “white circle” because the technologies at play in this installation are designed to shatter such traditional dimensions of sound and space. The ZKM Sound Dome used in “white circle” consist of 47 loudspeakers distributed through the room, which can be played using Zirkonium control software in such a way that the sound itself becomes more vivid, spatial, and plastic.

Raster-Noton juggernauts Frank Bretschneider, Byetone, Kanding Ray, and alva noto have composed multi-channel ambient pieces especially for the installation. The great majority of sound we encounter today is transmitted through one or only two channels. Multi-channel is too complicated (and expensive) otherwise for most systems.

Although the exhibition is called “white circle”, the installation actually comprises of two, or possibly three, shapes.

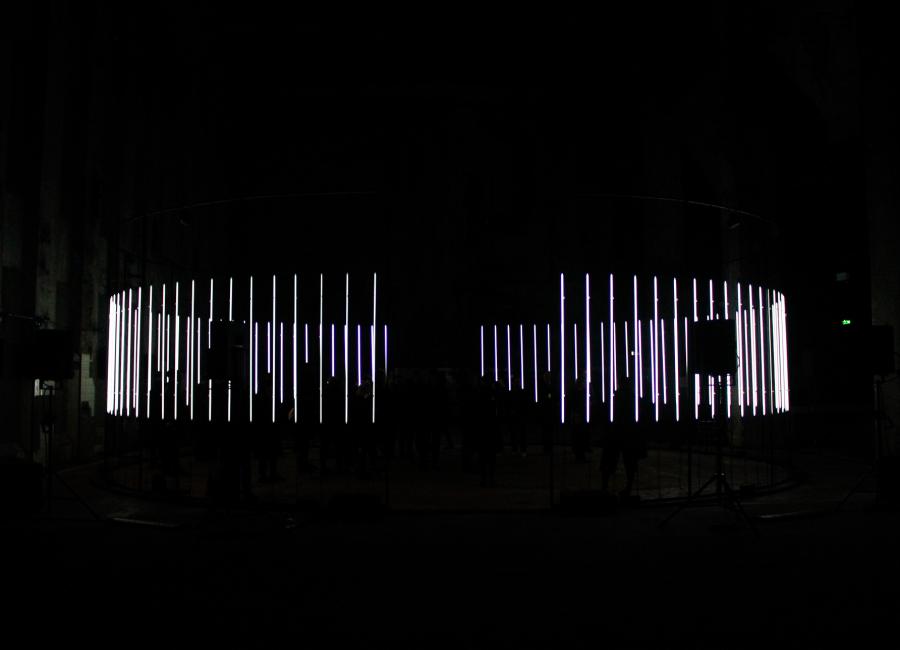

The first shape is the circle of flashing white lights, fortress-like in how clearly they demarcate the space: either you’re in the circle, or you’re out. The circle resembles a generator, except one that is self-contained, producing energy only for itself.

The circle is surrounded by a second, more invisible and amorphous shape: sound. Some of the 47 speakers line the outside of the white circle, creating its own circle. The pair of circles harken the image of Jupiter’s two plasma rings.

Plasma is the fourth state of matter. (The others are solid, liquid, and gas). Plasma is extremely electromagnetic, too hot to touch, too elusive to control. I think of plasma often when I walk through the installation. Very rarely have I been able to experience sound this spatially; it’s unnerving and has me grasping for otherworldly language to explain the sensation.

The installation’s audio-spatial field is so expansive that the sound seems at times to be the only true living thing in the space; everything else, especially us mere human specks watching reverently, are miniscule electrons to be absorbed by the sound.

At the same time, the loudspeakers create a very physical constellation of sound, and it is possible to follow a noise dart from one far corner of the space, swirl through the center somehow, and then appear all of sudden in the speaker directly next to you. The lights flash at the whim of the music.

Being in the circle feels like what I imagine it’s like to bathe in plasma—to enter a fourth state of matter.

Such is the bodiless nature of sound (and the needy, tactile nature of humans) that the production of music and the building of space to house sound go hand in hand. There has always been the desire to see or touch sound beyond listening—to render it more accessible and feel-able—because the exquisiteness of sound alone is almost too painful, too lonely, too demanding of some self-sufficiency that not all of us listeners can truthfully maintain. We need bodies. We need spaces for us to run and dance around in, even if they are only imaginary, in the way Brian Eno famously situated his music in airports.

Like Odysseus ensnared by the voice of the Sirens, listeners for all of time have craved the embodiment of music possibly more than the music itself. We love pop music because of the fleshy mortals behind the music; they seem touchable and knowable to us, and this makes the music more pleasurable to consume.

Computer or technology-driven music is interesting then because it has historically placed itself—or been placed by others—as oppositional to popular or “human” music: as bodiless, futurist, over-intellectual, Kraftwerk-man-machine, outer space…as cold.

But in reality, and as the geniuses behind Raster-Noton know, experimental computer-generated music is not so far from pop; it has probably never wanted to negate the human, but instead, sought instead to discover and produce new states of possessing a body and mind.

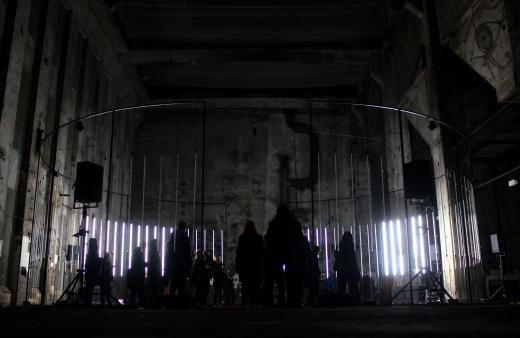

This is clear when watching the third shape in the “white circle” installation: the mass of visitors inside the circle itself. Some people close their eyes; their heartbeats slow down as a trance envelops them. Some people are anxious and agitated by all the commotion. Some smile deeply, tickled with ecstasy. And yet, there are some who, despite the loud drones and epileptic strobe lights, feel more sober and more awake than perhaps ever before.

More likely, each person goes through a spectrum of these sensations. That constant negotiation between trying to let yourself be absorbed by a foreign atmosphere and maintaining self-control amidst new sensory experiences is the very essence of experiencing music by Raster-Noton, and the very exercise many people subject themselves when they go to a place like Berghain.

It’s why so many people come back over and over again for a chance in the circle.

This weekend, Raster-Noton celebrates a 20-year legacy of using music, art, and technology to guide people through different, weird states of matter. The “white circle” exhibit is open in Halle from April 28-30. On April 29, Raster-Noton hosts a label showcase and party at Berghain.

* * * * *

raster-noton / "white circle"

Halle Am Berghain / Rüdersdorfer Str. 70, 10243 Berlin, S+U Warschauer Str.

28. – 30.04.2016 / 14 – 21h

More info: installation / party