BPIGShanghai

BPIGShanghai

During his lecture, “What is the Museum of Contemporary Art?” co-curator of the 9th Shanghai Biennale Boris Groys brought up the following scenario: We are immersed in a virtual world surrounding life, and in order to get away, to escape the glow of our computer screens, what do I do? I go to the biennale!

And, yes, that is exactly how I ended up in the audience of this lecture. I had no previous knowledge of the Chinese contemporary art scene or the biennale (reassuringly (?) co-curator Jens Hoffmann admitted that he didn’t either) and what better way to be a tourist in an extraordinary sci-fi city than via an international art exhibition under the guise of a workshop for art writers and journalists.

everyone's crush, Heinz-Norbert Jocks of Kunstforum International performs a live interview with Jens Hoffmann

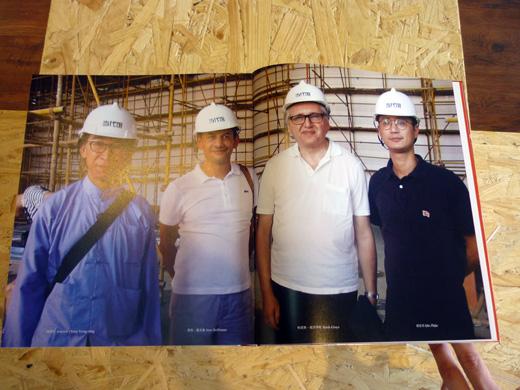

The biennale is the inauguration event for the brand new Power Station of Art, a former energy station that has been transformed into Shanghai’s newest museum of contemporary art. Chief curator Qiu Zihjie gave us a tour through the space one week before the opening event and it was shocking to see how much construction there still was to do. Most of the artwork hadn’t arrived, in fact even a couple of days before the opening only a small percent of work had been installed. Although it may be easy to build a building in China (it was amazing to witness a parking garage pop up basically overnight), the organization proved to be hasty and challenging; established Shanghai gallerists were furious they didn’t receive invitations to the opening, a massive iron ball was on the loose in the gallery posing a threat to visitors (it took six people and one red-faced, sweaty curator to get it under control), a rumor was circulating about a crying curator because their work didn’t arrive according to schedule, many artists were stressed and unhappy, and even Zihjie said, “I want to cry” when discussing the show’s financial situation. The Power Station of Art is a spectacular venue for contemporary art exhibitions, but perhaps its opening as a venue for the biennale is for the time being overly ambitious.

art can be dangerous, this was on the loose!

no time to make a proper sign, writing directly on the wall will do just fine

"hiding" the technology

How does the show measure up to the Berlin Biennale? Let’s compare co-curator of the BB Joanna Warsza’s question, “What can art do for you?” to co-curator of the Shanghai Biennale Jens Hoffmann’s question, “Are we asking too much of art?” The disappointing (to say the least…) Berlin Biennale showed us that overt political activism within the art context with little regard for aesthetics left viewers realizing that they could have saved themselves a trip to the museum by staying at home, reading the newspaper. It is this “gloom” of the biennale that tries to address the world’s problems that Hoffmann is responding to, suggesting that maybe we should just “let art do what it does best” (in his opinion, to surprise). According to his criteria for good art, however, overall, the works in the thematic exhibition fell flat. Many works attempted to respond to the scale of the building, but big does not necessarily mean good or surprising.

"One Thousand Hands" by Huang Yong Ping

At a dinner with some of the participating Chinese artists, the massive work in the entrance of the museum by Huang Yong Ping came up; most of us immediately wrote it off as an unpleasant monstrosity. One artist came to its defense, explaining its references to Duchamp, everyday objects, and Buddhism, but the heart of his argument was: "it’s big and that makes it interesting.” This attitude prevails not only throughout the exhibition, but in the city as well (just look at the skyline filled with massive, rainbow illuminated, but frivolous buildings).

the clever camouflage backside of the massive screen showing Jeffrey Shaw & Sinan Goo's work

Lima pavilion

The Inter-city Pavilion Project, in which curatorial teams from 29 international cities were invited to present their own projects, were in my opinion, the redeeming component of the biennale. The off-site spaces provided a welcome contrast to the pristine white cube of the Power Station; just off the ritzy Nanjing Road (home of the Prada store among others) are the unrenovated spaces housing many of the city pavilions. The participating curators and artists brought thoughtful works considering the relationship between the city represented and the context of Shanghai. Berlin’s pavilion, curated by Peter Anders, showcases the work of Raumlaborberlin, whose research revolved around the architect Richard Paulick who fled from the National Socialists to Shanghai to continue is practice in the mid 1900s. The installation includes a panoramic wall drawing of the architect’s work in Shanghai and Berlin and materials from his constructions in the former GDR forming a tearoom in which visitors can relax. The project brings together pieces of German and Chinese history as a means to reconsider the past in the present; this juxtaposition corresponds to the premise of the biennale, “reactivation,” more so then many works in the thematic exhibition. It is the context specificity of projects like this shown at the city pavilions that provide more than just a backdrop for the public to take photos of each other.

precious!

I have great respect for chief curator Qiu Zihjie, and I believe that he is a true visionary. The reasoning behind the curatorial strategy of the biennale is presented as a dense but dynamic map drawn by Zihjie; the form oscillates between a landscape, an industrial cityscape, a machine, and the anatomy of the human body. Movement through this hybrid body/factory/topography reveals complex relationships between his ideas about resources, revisiting, republics, and reform (the categories of the thematic exhibition), and his written description of his drawing is equally poetic and informative. He explains that the idea of reactivation “does not mean simply moving the power station to places further away from the city, nor does it just intend to introduce new forms of energy to generate power. Rather it provides an opportunity for us to reflect comprehensively on our lifestyles. The moment the old power station comes into use again, it injects into our social networks something of a spiritual pulse that activates the inner energy of the community rather than conventional electricity.” He believes that only by relocating the museum can the system be reset. Unfortunately for his vision, the mysterious and elusive biennale committee (the show is mostly government funded) was looking over his shoulder the whole time. Now that the foundation for the new museum has been established, it will be interesting to see what the future holds for the institution after the biennale and if they can maintain the resources to keep it going.