Pre-Interview: Philip Kojo Metz

Pre-Interview: Philip Kojo Metz

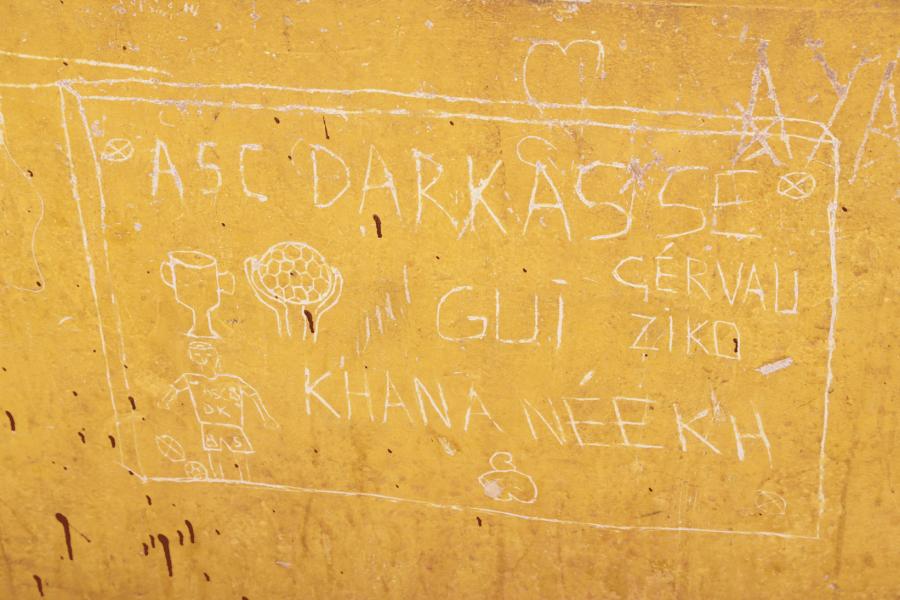

What started with a reenactment of a WOI battlefield in Cameroon between Germany and France has now developed into an ongoing project that alludes to several important topics, such as the effects of postcolonialism on identity, economics, politics and more. Documentation of the project Mimicry Games by Ghanaian-German artist Philip Kojo Metz will now be on display at Decad, opening tonight, Wednesday January 24 at 6pm. We spoke with the artist about the development of the concept of the project and his role in this process.

Can you tell us more about the starting point of your project Mimicry Games and your decision to integrate football?

The starting point was that I was asked to do a work in public space, that was in 2014, that was about examining the first World War. I am not a historian and I am not so familiar with the WOI, but I was involved in the German history of the African continent, and I was interested in finding out about the history of the colonial period. What role does the WOI play in the colonies, in terms of a German property? It is known that Germany lost its properties after WOI and I knew that there was a connection between the first and the second World War concerning the colonies. The colonies was a big topic, and I wanted to find out something -- to learn something. Since it was a public project, my mission was for people to get to know the history. So this was my idea: I wanted the people to be involved in the construction and deconstruction of stories.

I chose football because it is a language spoken by the masses; it is understandable for the people that I want to talk to through my work in public space. The first play that I staged was in 2014. It was in Cameroon and it had a reference to a battle between Germany and France that actually happened between 1914 and 1916. There was a War going on, between the colonies, between the properties of Germany and France. Cameroonian soldiers were fighting in the name of Germany and France. It was a test for me -- to see whether it works to stage it as a play. It actually worked really well, to transfer the battlefield to the playing field, taking it as a metaphor. Art is an image or reflection of the real world. You can still make real experiences, and with staging the battlefield I tried to see whether it is possible. The first game was to examine the history of Germany. It was a reenactment, but the scope was also much broader than that. In the second volume I wanted to have a more panoramic view of the topics.

How did you create the discourse around the play?

In the first volume I just wanted to stage the play. I had a commentator and I just wanted to show it. It was just playing with that notion of reality -- of making a statement that could be reality -- but also altering the reality. Most of it was the moment of irritation. Also in having this image: an imagine of the German players that were all black. For a long time it was an issue of to what extent foreign players could play on the national team -- not only African, but also Turkish people. When are they called Germans? When are they allowed to stand on the field and to sing the German national hymn and to represent Germany? This is a very interesting topic.

With the second volume I emphasised the topics in panel discussions. I took some of the images associated with football. For instance, with football, during the breaks and after the game people are always discussing the game. I staged these discussion rounds, parallel to the game. I gave some input, and put a frame. Each talk was about similar topics, which took football as a metaphor for political, cultural, historical and economical relationships. But each talk had a different emphasis. In total, 4 talks took place, each with different people in the panel discussion. I invited musicians, politicians, gallerists, journalists and football coaches.

Image credits: Philip Kojo Metz

Did you notice a different outcome for each talk?

I had a few questions for the musicians, for the gallerists, for the football coaches that worked in Africa. But they also came with their questions and their mindsets. These talks go for one to two hours and out of these talks it becomes a process, which I put together, reflect on and compare afterwards. We took topics that were emphasised in one talk into another talk. It has a sequence. But also, it is interesting to jump from one talk to the other. At the beginning I was not even sure whether I wanted to take part in the talks, but then it became an element of the work.

Why didn’t you want to be part of it in the beginning?

Because I wanted to be the observer first. Because I had questions, and I followed my curiosity and I was not sure whether it would work. And because I am not an expert in football, I was also insecure about what I could contribute to the topic. I had questions, but I didn’t have the answers. For example: Can I stage a historical reenactment through football? Can I take the battlefield to the playing field? Do we have the same topics? Can we compare them? What I observed is that we already compare them a lot. There are strategies, ways of identification, of imaging that are very similar. In the end, how the project evolves is that it is about a process that I went through. That’s something that I also like about the project.

What kind of topics were you trying to bring up in the discussions?

First of all, I wanted to put people together who are not usually together in a panel discussion. This alone already puts the discussion in a certain direction. In Berlin we got a journalist from a football magazine, Christoph Biermann; Gernot Rorh, who has experience as a footballer and national team coach in Africa; and the filmmaker Alex Moussa Sawadego, who has a passion for football. For the filmmaker, the reception of football was interesting; for the coach, the players where interesting, the training methods and the strategies, or the philosophy of the players -- the structure of the business. For the journalist, there were other topics -- he had a reflective view on it. In Senegal and Dakar my question was how politics was involved in culture. This was very interesting to discuss with the two musicians that participated in the talk. They use their tools to change society, or maybe at least try to be a medium between the people and the power. They see themselves as an amplification of the needs of the people. I also discussed pan-Africanism with them, because nowadays football is also a tool of politics. What I find interesting about using the game of football, is that it is such a big metaphor for life. By taking this topic, you are addressing so many nations at the same time -- integrating nationalities and the borders of countries.

Image credits: Philip Kojo Metz

Is there a certain outcome that you are aiming for with the work?

I have certain questions that are cultural, economical. I am following my curiosity. My idea of outcome would be that we understand more of these relations and bring various knowledges together. If I go into a panel discussion, I don’t go with the knowledge because the people I invite are experts. I have more questions than I have something to say. Whether I succeed or fail, I don’t know. I have a feeling that there is something in this image I am staging. There are a lot of aspects in staging this -- in the claim of it. I claim that it is like that, and then I am trying to find out whether it is true or not. Then I find out that what’s in it is interesting for me and I can use it in the development of the project. There are topics in football that are not so useful for me; they are still interesting and maybe they will become part of the project at a later stage. For example, there is a lot about the psychology of football that I find very interesting -- the focus and the narrative. This topic developed through the process of the work. There are a lot of topics involved in the work and now we are at a stage where it can become interesting on a scientific level. There are people that examined the topic of players that are sold to Europe on a scientific level. For me, the outcome that I would wish for is to connect various levels. What I feel that can be interesting in artistic work, is that it is history related, science related, and it breaks down the message to present it in various levels. You have the image, and you already show something, but you don’t have to explain it or write a book about it. How can you go deeper? And what do you find on the way? What can I offer as a shared experience, as a participation and discussion? I am interested in bringing politicians together with footballers that have a lot of knowledge about the body and psychology. A coach has a lot of knowledge about strategies; I want to bring this together with musicians. The danger can be that you have so many topics to cover, that it seems to be irrelevant. In the end, I want the outcome to be relevant.

Your role as an artist is much more related to the role of an organiser, a mediator, and is curiosity driven. You would make different decisions as a politician or a musician. How would you differentiate your role from a politician or a musician in this process?

What is interesting in art is that you can bring the battlefield to the playing field. You don’t have so many restrictions. I can play -- compared to a politician who has a lot of responsibilities. I think that there is actually more in common in decision making, than in the process of decision making itself. I don’t have the position that if I say a wrong word, it will have this much of an effect. I have the luxury that I can experiment, and it is actually expected of me. I feel that it is a very good position.

Can you tell us more about what you will be showing at Decad?

I was invited to present some kind of documentation of what I have done up until now with the Mimicry Games. That was the emphasis. But I am always interested in the future. I always look at what I can do with it and what can come out of it. I am very happy to actually review what I have produced and to think about presenting it. And presenting means to make it accessible for other people. In this process, it is very helpful to work with other people and to get feedback. I am very happy to be working with Rachel Alliston from Decad, because she has a different view from mine, and I am really interested in this -- in seeing how someone else perceives it.

Another aspect that is really important to me is finding out how it can lead to a new level of the project. I see it as a chance to open up the discussion more in the direction I want to go. We aimed for inviting experts from different fields, which can lead the project into a new direction. My plan is to take the 2018 world championship in Moscow as a topic. I would love to invite the Invisible Borders project from Nigeria (http://invisible-borders.com). I want to take a trip with them from Berlin to Moscow and discuss post-colonialism in the East. The Invisible Borders project has become very famous at the moment -- they currently have an exhibition at Centre Pompidou. I am in contact with one of the core team members and we got him for the project -- he is supposed to take part in a panel discussion. There will be some topics coming up during this exhibition that are relevant to where I want to go.

Forgotten Futures is my slogan for the show at Decad. Personally, I see that, through the process, it became clearer that the 2014 game represents the past, 2016 is the present, and 2018 is the future. The Forgotten Futures project is interested in visions and identifications of the past. What images did the people or nations have that were destroyed or forgotten?

The videos were the starting point for this exhibition. These are videos of the games staged. Then there are also two team photos, which appeared through the process. The work is already existing, but newly staged. Only one new photo will be added. The shirts that are on display here also appeared through the process. The names that you see on the shirts are African heroes that came out of the pan-africanism movement. Football was used as a tool to enforce the pan-africanism movement through the names staged here.

Image credits: Philip Kojo Metz

Do you see a different development in topics that you have been addressing over the last 4 years since the project has been in process? For example, the topic of the influence of post-colonialism is much more talked about nowadays.

When I started the project in 2014 there were certain circles already discussing the post-colonialism topic for a longer time. My other project that is about German history in African countries started in 2010, and back then nobody was talking about it. It was very hard to get funding, for example. Nowadays, there is more of an openness, and more of a knowledge and interest in these topics.

What will happen after the exhibition at Decad? Are there certain directions you would like to take the project in?

In 2018 I would like to examine the topics that come out of the project. I want to double check it on a scientific level -- discuss the aspects on a deeper level. This would be my wish, as well as to have it shown on various levels and occasions, and in various sizes. For me, it is interesting to show these images and then to push the discussions -- to ask questions and to have these questions asked. It is not only about giving answers. Often things are taken for granted. For example: why is there not an African team playing in the European championship? They belong to Europe, to a certain extent, and Europe has a lot of claims and property in Africa. France controls the money system, and also the flow of national resources. Even the US has a claim in that. It becomes especially obvious in the French teams, as they have no problem selling these national players to the team. Senegal is not considered a part of France, yet somehow it is. Where is the border? And where is the border that we want to state? Why is it so normal that we can travel to Africa and Africans cannot travel here? There are some really tough questions in what I am staging here. There is a joke in having black people wear the German jersey, but it is also very serious.

Do you feel that you are able to ask these questions because you are half Ghanian and half German?

I think so, yes. It is unfair, but I have an advantage there. I can talk from various perspectives. I grew up as an Afro-German in the Black Forest, so I know how it is. I don’t claim to be the only one that can claim this. I don’t believe in the color of skin in that aspect. I believe more in things that we have in common, than in separations. But still, if you talk about certain topics it is not so easy to talk about it if you can’t identify with it -- if you are not part of this image, of this certain group. In my staging, I’m saying that talking about these topics does not depend on skin color -- which I know is dangerous and risky and sometimes uncomfortable. I still have an advantage, because I have a different attitude and experience, which is also part of the work.

I met this guy from Turkey who told me a story that I found really interesting. He said, it is better to tell a story from below looking up. People react differently and it is actually more fun. You can’t do a joke from above. If you put yourself in the position of the victim you always have more sympathy. If you ask questions, you also have more sympathy. It is a different attitude if you ask questions from below. For me, I hope that I make people curious, not only by talking, but also by exchanging images.

***

Philip Kojo Metz

'The Mimicry Games'

Opening: January 24, 6pm

Duration: January 25 until March 31, 2018

Decad

More info