Malwina Niespodziewana's "Comic Gold Haribo"

Malwina Niespodziewana's "Comic Gold Haribo"

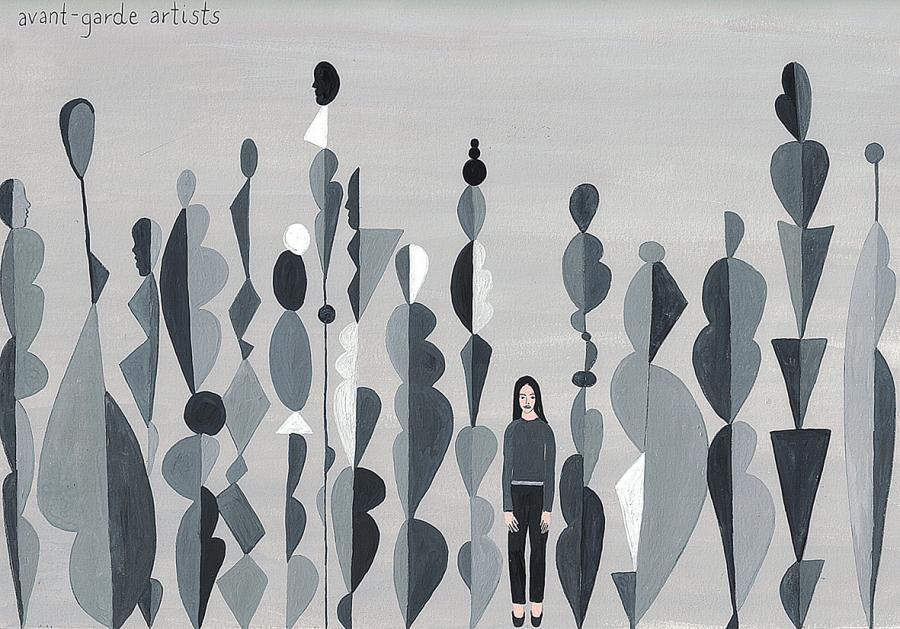

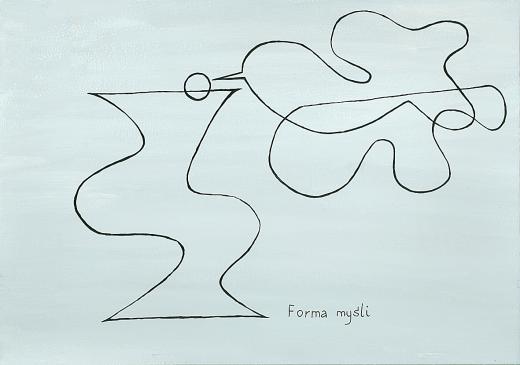

The Polish artist Malwina Niespodziewana recently exhibited her latest series Comic Gold Haribo at Maniere Noire in Berlin. In the 30 drawings, the artist explores scenes drawn from her work, her family and her surroundings, while at the same time addressing universal themes. The apparently minimalist layout of her work offers the chance to delve into a deeper, richer universe of visual cues and words, that create the weft of a powerful reflection on our own existence. We had the chance to chat about her work and the inspirations behind it.

Malwina Niespodziewana, "Comic Gold Haribo" @ Maniere Noire

Can you tell us why you chose the Haribo bears as reference in the title for your work? Other than relating this term to Berlin, were you perhaps attracted by the idea of seriality, and the small dimension of these candies, which resembles the small proportions of your drawings?

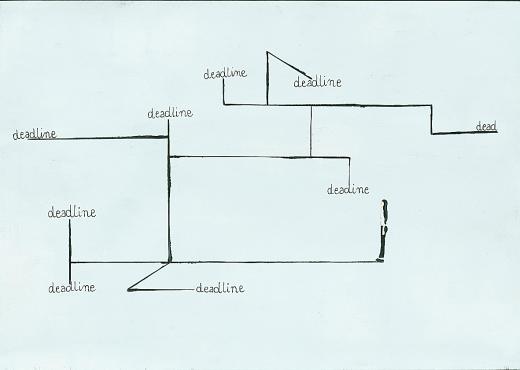

This is a very curious observation! The formats of the comics are small, making it easy to carry the sheets of paper around with me and draw systematically. Giving the series a stringent format from the beginning became an important element of the work, and I published the images on my blog on regular basis: every Tuesday of the week, throughout one year.

The decision to include in the title the word "Haribo" was made years ago, more precisely on July 2011, in Berlin, during a nighttime talk with friends on our way to the next Milonga dance. I was truly bewildered by the whole conversation and its absurd point. Although I cannot reveal the details of the situation, I can say that I was deeply impressed by the words that were spoken and their possible interpretations. It is also worth mentioning that my interlocutors were a poet, a playwright, and an actress. There was certainly some additional magic too, an ingredient that only Berlin is able to add to the whole. Interestingly, almost all the Berlin-inspired works (the three-part Haribo Comic, some of the fairy tales and drawings, etc.) have been exhibited in Berlin again, as if enabling me to extend my gratitude to this great city.

The small dimension of your series is a nice contrast to the powerful messages they convey. How do you manage to reach such a balance in delivering a message in your work that is effective and rich in meaning, and yet not suffocating in its physical representation?

All solutions are brought by life itself. Every scene in the Hariboseries has really happened, and so each drawing is a situational record. The rule is to be attentive to life. And I like to both live life and draw from it.

Looking at the drawing where a woman has her arms stretched to hold a little girl and a man, a possible interpretation that came to our mind was the imbalance between the possibilities that men and women have in live. Can you think of any moments throughout the series where you consciously wanted to highlight a valid issue about the role of women in our society in contrast to men?

The drawing you’re referring to is from the last series—Comic Gold Haribo, whereas the essential "female awareness" emanates from the Comic White Haribo, the drawings of which describe my everyday life—the mother, the artist, the partner, sporadically accompanied by my daughter's observations. After seeing the White Haribo, many women told me that these works were about them, and that they could identify with the character of the comic.

I am a feminist, but as I always add, in contrast to other feminists, maybe, I live in a very traditional relationship—with a loving husband to whom I’ve been married for twenty years and a loving daughter. However, women's causes are and always will be my topoi.

From a personal perspective, the series Comic Black Haribo is of great importance, possibly because it was created immediately after I lost my mother. These drawings are a record of conversations that took place between my daughter and me, in which I explain to her that people eventually die. At a time when loss was so present for me, I could not remain indifferent to my daughter’s questions about the end of life. While completing these drawings, I could feel a very distinctive shift of generations taking place, because being exposed to such difficulty made me represent myself in my drawings as a child, too. After that, working on the Black Haribo was a way to work through my own trauma and grief. This series was never exhibited in its entirety; only three people have seen it.

The penciled-in words in your mother tongue within your drawings words are very interesting. Are then any words in Polish that you would like to redefine and update, to give them a more contemporary meaning?

In the Comic Gold Haribo, apart from drawing real situations between people, I mainly focused on myself, hence the word “gold” standing for luxurious. In my opinion, it is indulgent for a mother to concentrate on herself.

Haribo is of a very broad structure and it lays open numerous topics. While unfolding from drawing to drawing, it not only introduces a new issue or poses a new question, it also invites the viewer to take part in the discussion. Haribo is not a classic example of comic. There is no temporal continuity in its narrative timeline. Also, it does not have a typical beginning, development, and end. Images interplay with text on many levels and divulge their specific background and cultural context: my dilemmas as the author and my position as a woman and artist.

My artistic projects often begin with the written word in modes such as poetry, diary, or biography. My two large projects are good examples—Erna, a series of works about the Polish poet and painter Erna Rosenstein, and Kobro, a kind of gesamtkunstwerk based on the life of Katarzyna Kobro, a Russian-Polish-German avant-garde sculptor. The latter was a long-term project that included research, reading diverse biographies on Kobro, investigation, taking notes, meeting and interviewing people. Three pop-up books (comics) were some of the artistic objects in that series. One of them was based on a manuscript (never before published) of Kobro's daughter, Nika Strzemińska.

I enjoy keeping notes, whether in drawings or words. I’ve been keeping a diary for over thirty years, recording what I’m currently working on, what I’m reading, where I am, who I meet, and what happens. In my journal I capture not only personal memories, but also moments in the artistic life of Cracow. Salvaging things from what becomes the past has become a habit that I often find useful.

How has been the time for you whilst working on this series? Have you experienced a different way of working that made you perhaps more productive/less productive? Have you found specific places where you feel you can work better than others - e.g. Cracow, Berlin? And why do you think that is?

The creative process of the overall comic was dynamic. I never wait for a special time to make creative work. I’ve never thought about comfort during work. In fact, most of the drawings were created in times that I was coping with everyday conflicts of a practical or spiritual nature, or relating to my own body, family, society. I am always able to find the time and place to do my work, to think without interruption. White Haribo was created at home, with my little daughter nearby, Black Haribo was noted in a sketchbook and everywhere, whereas Gold Haribo was created in my beautiful new studio. I always have drawing tools and sheets of paper handy, sometimes prepared with a background. Apart from that, I always carry a sketchbook with me in which I take notes and sketch. I write or draw any time an idea comes: at the doctor’s, while shopping, or when meeting with friends. However, large works made in multiple stages are obviously executed in the studio. And then I take a complete break once a year and go on holiday with my husband and daughter for six weeks.

* * * * *

Translated from Polish by Majla Zeneli.

Artworks © Małgorzata Malwina Niespodziewana