Book Hook: Atlas Projectos

Book Hook: Atlas Projectos

Interview with Nuno da Luz of Atlas Projectos

The first installment of Book Hook spotlights on Berlin’s publishers begins with Atlas Projectos based in Lisbon and Berlin.

How did you get involved with Atlas Projectos?

André Romão, Gonçalo Sena and I met in college and wanted to create an output for interests we shared both as friends and practitioners. We studied graphic design together but worked as artists and from the start there was a need to create something in between. This was around 2007 and there were not many publishers in Portugal. There was a fanzine culture tied to the music scene and art publications were the typical institutional catalogues. Although there was a tradition in artist books, these were mainly handcrafted. We felt there was a huge gap in between all of these.

What was your first project?

Our approach was conservative at first. We felt that each publication must be edited, curated and designed by the three of us, and of course things have changed since then. The first project, ATLAS Projecto de Desenho (2008) was about drawing. There is a tradition of using drawing as a conceptual tool and many Portuguese artists deal with drawing as a theoretical foundation for the work they do. Our funding came from foundations, and we thought that this would be sustainable: we would sell enough books to fund the next project, but this was not the case. It was only when our primary rule of being both editors, curators and designers changed – when André Sousa asked us to design a book for him and Tobias Hering – that we resumed work. We designed Fabel/Fábula/Fable together with him, as part of his residency at Künstlerhaus Bethanien. We then realized the potential of actively supporting the books we're involved with, even if we didn't set all parameters.

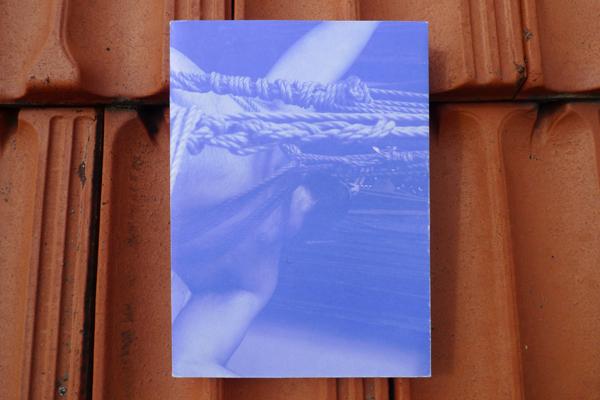

ATLAS Projecto de Desenho (2008)

And is this why the group moved to Berlin?

We were already here. I came to work as an assistant to an artist to get things started for myself, and my partners came for similar reasons. Still most of our work is tied to Lisbon, and we have close connections to people there who we went to university with or are on the same wavelength with. At the moment I am the only one based in Berlin; we are always moving around.

What was your most successful/pivotal project?

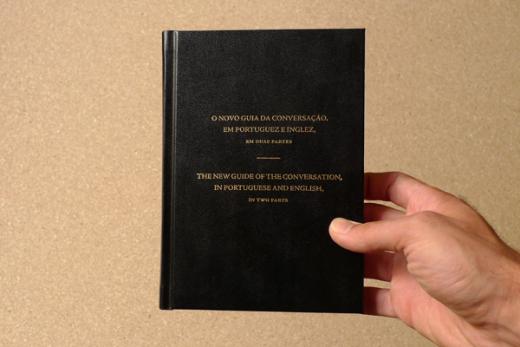

The New Guide of the Conversation on Portuguese and English (2010) is sold out! The book was first published in 1855, and we first learned about it in Berlin. The back of a record cover (by New York band Amolvacy) we came across in a record shop here had these strange quotations in a crude, broken English, attributed to two Portuguese authors whose names weren't familiar to us at all. When we looked them up later we found the pdf of the original edition, made available by different libraries both in the US and the UK via Google Books. After further research we found that the book can be easily found today in English speaking countries under the title “English as She is Spoke”, but nevertheless the original edition is not available in any library in Portugal. Most versions known as “English as She is Spoke” focus solely on the English and get rid of the Portuguese counterpart. So, to reprint the original unabridged meant making it available again, first of all to a Portuguese speaking audience, but also focusing on the linguistic and poetic potential to English readers. This project made us question our role as publishers. Before we had been using the words editor and publisher in the same sense (also, in Portuguese there is only one word for the two) but now we see more of a distinction.

The New Guide of the Conversation on Portuguese and English (2010)

So what is the difference between an editor and publisher for you now?

Editors play a more active role in shaping the content with writers and have more authority over the material. Being a publisher stems from being a designer, not so much informing content but definitely influencing form and how that form/content circulates. The definition of publishing is “to render public” so to put something out there, to communicate. In some cases books we designed might otherwise stay forever in the institution that funded it.

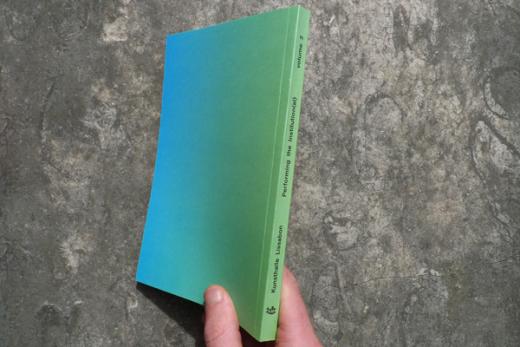

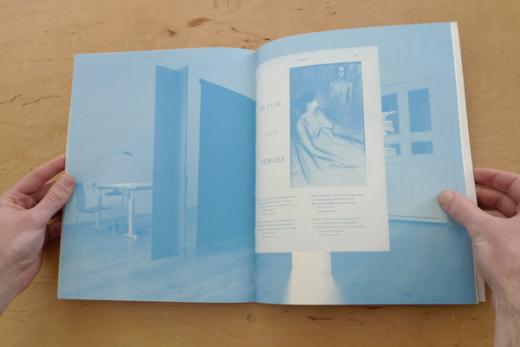

Performing the Institution(al) vol. 2, Kunsthalle Lissabon (2012)

How do you fund your projects?

Some catalogues pay for themselves, in other cases we get paid as designers. This way we are able to connect what we do as designers on payroll to our role as publishers. It helps having an institutional system that accommodates publishing as part of their business model. But we manage to make it happen through smaller things as well and by thinking about each project according to its own set of rules. It helps working together with friends who are also professionals in this field, and by doing so one project leads to another. We don’t always work for Atlas because we take time off to do other things.

How do you decide which projects get the “Atlas Projectos” label if you are all working on projects simultaneously? You showed me one publication that is an exhibition catalogue you made for an exhibition of yours, but there are also catalogues for shows in which you worked as a team of graphic designers. There is quite a range.

There is a common feeling among us about which projects get the label. We want to help circulate and distribute even if the audience we're talking about is somewhat limited. It's mostly about creating a sense of commonality, of actually sharing the process of making. People have approached us with very specific ideas about what they want even before they work with us, and those cases don't usually work their way into our roster.

I am trying to find a connection among your different projects and it seems like the goal is to introduce what is happening in Lisbon to a broader audience. Would you agree?

Many of the projects happen by chance, and we try to be open to wherever they lead us. Most books relate to the Lisbon scene because of our connections there and our background. It's not that just because it's happening in Lisbon is rich enough to render content, it's necessary to create discussion, and we want that to happen not only there but in fact anywhere, together with our friends and peers. Our starting point is mostly this set of revolving people that we work with and call friends at the same time. Lisbon works as an axis, as much as Berlin has as well. Then there was the New Conversation Guide project which had been conspicuously republished in the English speaking context, and is also known in Portugal through American and British republications. So we are bringing things into and out of Lisbon, but bridging some kind of common ground.

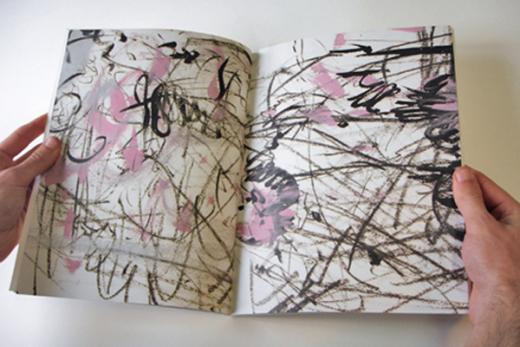

Paintings x Painting, Hugo Canoilas (2011)

What should we expect to see in the future?

Later on this year, we will publish a flexi-disc by Lisbon-based artist Joana Escoval, who has been working around a pair of olive trees she donated to the Botanical Garden in Lisbon, in 2007. This is a 7'' acetate of ambient sound she recorded next to the trees, and the cover will be documenting this project from its start until today.

Also, as a group we have been working on an editorial project for two years now, but have not found an appropriate physical form for it.

Can you speak a bit about this project? Or is it a secret?

It is a secret for now. But I will say that it relates back to drawing.

Why is publishing important today?

The million-dollar question and a difficult one to answer! It is about circulation. Even if we're talking about a very small audience, it's mostly engendering a process of exchange and feedback. This can happen in many other shapes or forms, but given our own practices as artists and our education as graphic designers, we are devoted to the materiality of paper and the printed page as preferred vehicles for how we like to start conversations.

Ámanhã 1909-2009 (2009)