Have you met... Bernd Trasberger

Have you met... Bernd Trasberger

In the center of the recently renovated and reopened Berlinische Galerie is the exhibition “Radically Modern: Urban Planning And Architecture In 1960s Berlin”, which takes a comprehensive look at the architecture of East and West Berlin, and its development in the post-war years of division.

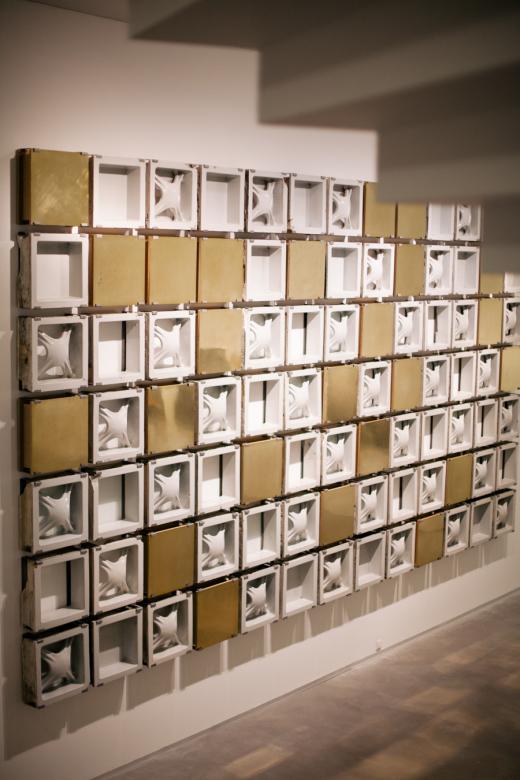

One of the most eye-catching and curiousity-inducing pieces in the exhibition is the massive artwork by Bernd Trasberger, made from the elements of a typical modernist façade of a former department store "Hertie" in Neukölln.

This artist, whose work is closely tied to architecture and inspired by modernism, shared a very interesting story about the making of this imposing piece, as well as some of his thoughts on the issues surrounding the ways the city deals with this architectural heritage today.

Tell us about your work ("Hertie") currently displayed at the Berlinische Galerie.

It is actually a part of the facade of the Hertie department store in Neukölln, which was demolished in 2009. I salvaged a part of it. It is a typical kind of grid facade that was used mostly for department stores. I was living not far away from that building, so the facade called my attention, whenever I passed by. One day I saw that they started to tear the building down, so I wanted to safe some of the ceramic elements the facade was made of... This is how it started.

What is your relation to modernist architecture / architecture in general?

At first I was interested in landscape – mostly in the dichotomy between artificial and natural landscapes. Later my focus changed more towards man-made landscapes, urban environments. At the same time, I was drawn more and more into abstraction, which is also a basic tool or means of modernism. That is how I sort of slipped into the topic. Especially in Western Europe, modernist architecture is still quite dominant in public space due to large reconstructions after the War. It is the kind of environment that we grew up in, so it is a basis from which we start to experience architecture.

If you deal with architecture in cities, somehow you cannot escape dealing with moderism, it is such a big issue. And of course, nowadays it is interesting that there is this kind of time-lapse. In the seventies, a lot of historical quarters were demolished to be rebuilt in a modernist way, and nowadays a lot of this modernist architecture is being demolished again. In a lot of places they actually rebuild historical architecture or pre-bourgeois cityscapes. I think it is quite interesting to observe such a development that moves in circles. In the end I am fascinated by the change of our surroundings in general and the passing of time, that so becomes apparent.

In what way is modernist architecture in Berlin an issue today?

Well, if you talk about urban change, Berlin has been a very important laboratory in the past 25 years, and a lot of discussions revolve around modernist architecture. Everyone seems to be already bored by the embarrasing Stadtschloß – Palast der Republik – Stadtschloß again – discussion. But still it is a very emotional issue. The whole Kunsthalle-debate began there, when artists claimed the structure as an exhibition space . The re-use of abandonded architecture is a central motif in the succesful rise of Berlin as an artistic hot-spot. Berlin went through all stages, from improvised club culture to environmentally friendly townhouses, and it keeps on changing: we had “Based in Berlin” instead of the Kunsthalle, we will get our Hohenzollern castle back and collectors live in lofts on former techno-bunkers. But it keeps on changing: one day they might re-construct the Palast der Republik, tear down the Fernsehturm or start to use Tempelhof again, while fashion fairs move to BER.

Sorry, I will be serious again: take a look at the high-rises around Kottbusser Tor - these were looked down upon, nobody wanted to live there. But then the area became interesting for cultural producers and now is totally gentrified... Whether you like it or not: as an artist you are always involved in the process of urban gentrification, and since we often have our studios in former industrial sites, a lot of modernist structures are involved in the play. I had to leave my last studio on Naunynstraße because it was turned into luxury lofts. Now I work in a BBK studio at Naumann Park – an industrial site, which was bought by Berggruen Holdings. So, it remains to be seen if that area can be established as a site of cultural production, or if we have to make way for luxury dwellings again some day.

There is so much going on in Berlin, there are so many important buildings, as you can also see in this exhibtion. It is interesting to ask yourself if it is always the right way to discard yesterday's ideals and move on to another fashion. It is actually something that modernism did in a very radical way. The question is always – what do we get in exchange? For example, this facade was from a type of department store, and now they changed it into a standard shopping mall, with H&M, Starbucks … Always the same set-up of companies. It is investor architecture, driven by the need for profit. In most cases, a lot of people hate modernist architecture and they are happy if it is being demolished. But if you look at what we mostly get in exchange, it is for sure not always better.

How is your work referring to these issues?

Bernd Trasberger, Hertie, 2009 (photo by Marlen Mueller)

Basically, I want to investigate the value and the potential that we see in these buildings. I want to isolate them from the vortex of time, and place them in a setting in which we can look at them differently. I hope that these artifacts can become catalysts to motivate thinking and discussion about some of the aforementioned issues. When I was looking at this facade, I noticed the abstract grid pattern. And since a lot of the architecture in the sixties was very much related to minimalism, I first experienced it as a minimalist work. But if you think about architectural history, it refers to a certain type of facade designed by Egon Eiermann in the early sixties, which was used particularly for department stores. A lot of other department stores started to copy this type of gridded-box-building. When I saw that they were tearing Hertie down, I thought there is a certain type of historic reference in these elements, and I therefore wanted to save them. When the facade was being torn down, a lot of elements broke. So there were gaps and voids in my re-arrangement of the facade, and I wanted to fill them up, referring to a Japanese technique called kintsugi. When a ceramic vessel breaks, or it has cracks, it is going to be repaired and the cracks are being filled up with gold. The idea is to make the object even more valuable because of its traces of damage. The marks of history are seen as a value, not as a detriment. And now think about how it goes in Western society; if things, objects, or buildings show traces of wear or decay, they are easily being discarded or demolished. So that was my idea - to save parts of the facade, and then increase the value of it by repairing its cracks with brass plates, and show it in a museum as a very monumental piece. It almost appears as if it is a part of the Pergamon frieze - an antique, precious object. I like this kind of shift because before it was hanging on Karl-Marx-Strasse for 40 years, dirty and in a bad condition. Nobody was looking at it. It was just run down and ready for being demolished. Now it is hanging here, and it is actually a precious piece, that we talk about.

I made the work in 2009, and I showed it in a solo show in W139, an art space in Amsterdam. In that exhibition, there were several pieces that related to each other and dealt with the re-use of historical fragments. Here it is more autonomous. For example, this whole Berlin connection was not really important in Amsterdam Here it is also connected with the archival photograph, which we lent from the Heimat Museum Neukölln. Even though “Hertie” is an older work, for me it is interesting that it is activated again because now it plays a different role, and it has something else to say in the context of this show and the modernist architecture in Berlin in the sixties.

Which aspects of modernism do you personally value the most?

Of course, you can criticize a lot. A lot of architecture is just built very poorly. That is why it has a very bad reputation. What I like about modernism is the social aspect. If you think about city planning, and you can also see some of the designs here in the exhibition, there were always facilities for the public included. You have public libraries, swimming pools, and it is a very utopian kind of thinking, being able to create a better environment for mankind. If you look at the ways the cities are being developed nowadays, sometimes I really miss this kind of utopian, idealistic thinking, because nowadays it is mostly fueled by capitalism. Companies actually define the appearance of our cities. There are some other things, but I think this is the major aspect that I appreciate. And if you look at this Hertie facade, it is actually made very carefully; the cross-shaped ceramic form is quite complex , though it was made for a mundane department store. It is a different type of craftmanship, no computer involved, although these organic shaped curves make you also think of Zaha Hadid somehow. I tried to find out, who actually designed these elements, but I was unable to track that down. When researching the history of post-war architecture you will find a lot of black holes. Sometimes it feels as if we know more about the Antique than about that recent past. I would still love to find the person who designed the elements of this work. Imagine: An old man in his eighties finding his old design being valued in a public museum!

Do you think that this exhibition could change the way Berlin's architectural heritage and modernist architecture in general is perceived and valued?

If you look at the works in the exhibition, there are a lot of buildings that do not exist anymore. I think it is good to show those designs, especially to the younger people living in Berlin. It is typical for Berlin as a globalized metropolis, that a lot of young people living here do not know or care much about the history of the city. Especially when you talk about changes that cities undergo, modernism plays an important role. It has changed the faces of the cities in the fifties, sixties, and seventies, and now it is the reversal change because this architecture is disappearing. It is very important to show the power of this kind of city planning. You could say that there were more radical things going on in the sixties in other parts of the world. Berlin was very much dominated by the two blocks facing each other, so everything that was happening in Berlin is overshadowed by this political situation. But that is the topic of the show, to have a look at the sixties in Berlin. We see imaginary architecture that has never been built, and buildings that do not exist anymore. We feel the visionary power that people had at that time and we add all these imaginary structures to the real Berlin, that we inhabit today.

* * * * *

“Radically Modern: Urban Planning And Architecture In 1960s Berlin” @ Berlinische Galerie

Alte Jakobstrasse 124 - 128, 10969 Berlin, U8 Moritzplatz

Wed –Mon 10h–18h, Tuesday closed

Open through 26.10.2015